"Life is only worth a damn because it's short. It's designed to be used, consumed, spent, lived, felt. We're supposed to fill it with every mistake and miracle we can manage. And then, we're supposed to let go."

Yup. And then, apparently, we’re supposed to oil-wrestle, emotionally regress, and tack on a finger-wagging message about living life to the fullest before death finds you while pretending it's some revelatory philosophy class.

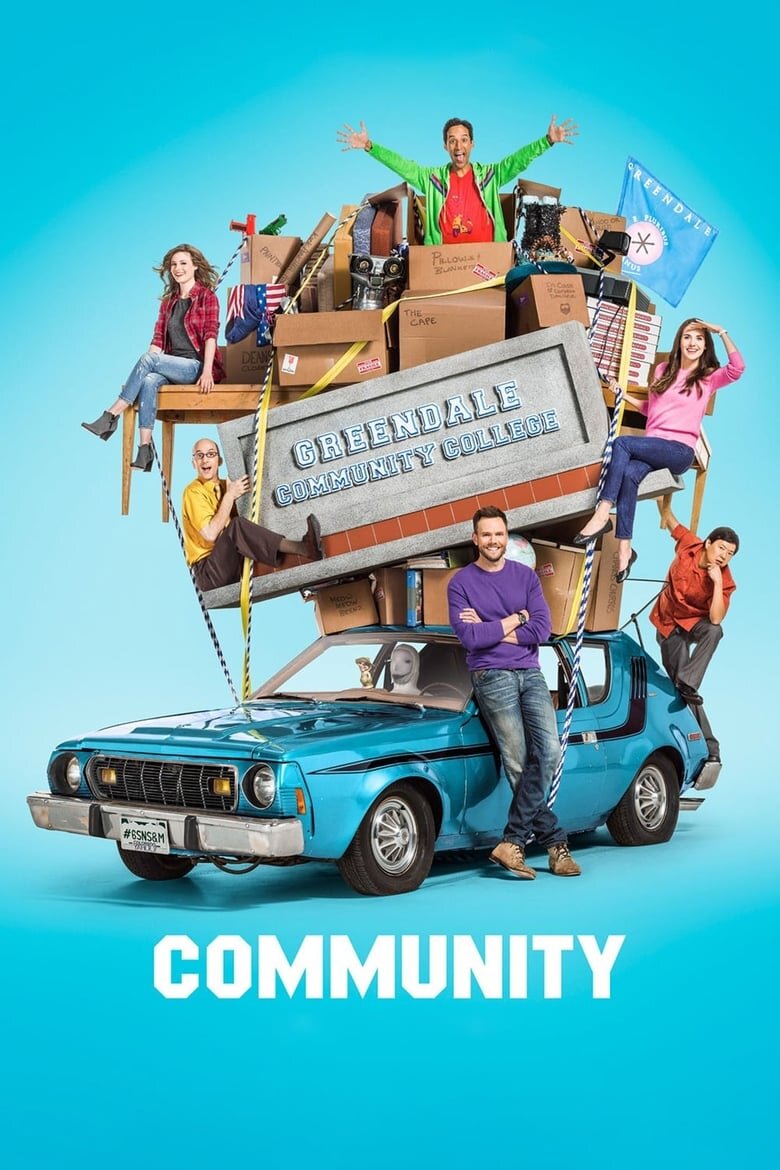

"The Psychology of Letting Go" is probably the safest Dan Harmon has ever played it, which—when you think about what

Community usually pulls off—feels like a letdown. For a show that tends to flip sitcom conventions on their smug little heads, this one's practically

Hallmark Presents: Death and You, complete with awkward hugging and the inevitable sitcom-patented THE MESSAGE™.

The Jeff Winger arc here is just... baffling. He’s somehow regressed from his more thoughtful, emotionally textured version we saw in

“Accounting for Lawyers”, where he grappled with the toxic allure of his old life. Now he’s back to being petty and cartoonishly stubborn, derailing someone else’s grieving process just because his cholesterol levels dared to exist. The lesson he learns about mortality? So heavily foreshadowed it might as well have been subtitled “Important Character Growth Coming in 3… 2… 1…” And I mean, I get it, sitcoms gotta sitcom. But Jeff’s character felt more nuanced even in the second half of

season one. It’s honestly more satisfying to swap this episode and

“Accounting for Lawyers” in your rewatch (which was probably intended tbh, considering how it's one episode after this one in production code); that way, his development has some semblance of continuity.

Then there’s the Annie/Britta conflict. Or more accurately, the Annie/Britta catfight that's clumsily disguised as a gendered satire. Now, I usually

love Britta and her tough-as-nails attitude. She’s insecure, surly, and neurotic in all the best ways that even remind me of my former liberal self. But holy hell, this episode veers into smug self-contradiction. She accuses Annie of “jump-starting date rapists” to make a bigger profit, only to literally do the exact same thing a minute later under the guise of proving a point. And then after the exploitative spectacle they create—played for laughs, mind you—we get the cherry on top: "men are gross(er)." As if that neatly closes the loop on the hypocrisy. Like, lady, you jumped straight to the horrific idea of rape criticizing your friend for using her body to earn money. You don't get to make a sexist remark about my gender being grosser with your tactless projection. It’s frustrating, because the episode wants to have its cake (oily fan service) and eat it too (moral high ground), but all it ends up doing is undercutting its own message.

And it's funny because my first thought seeing that catfight in the episode was not even how hot it was, but that maybe they shouldn't do that sort of thing in front of a bunch of men specifically because of the eroticism you're trying to criticize, but hey, I'm the gross one when you ended up using said sexual exploitation to make money anyway.

Even the theme itself on living life to fullest instead of focusing on death feels shallow in its execution and generic in its point made. It's perhaps a coincidence, but it's kinda funny how some of the other shows I'm watching this month (including the visual novel I'm playing) have similar themes of death and how we deal with it.

"Mad Men" had Don Draper going through spiritual death (and then actual death) in

"The Doorway" two-parter season 6 premiere;

The Sopranos' season 6 premiere,

"Members Only", literally opens with William S. Burroughs talking about the seven souls from death; and of course,

"Kara no Shoujo 3," the visual novel I'm playing that's littered with

Dante's Inferno poems, opening with a memorial grieving over a prominent character (to say the least). People can sometimes connect patterns in all the most random and non-related manner, but what is related is that their thesis on the inevitability of death and how we deal with it and moving on from it is still undoubtedly far more compelling than the weak writing of this episode, period, with its cliched message on how we should embrace living before death - yeah, thanks, Seneca, real armchair philosophy there.

Ironically, the most grounded character in this mess is Pierce, of all people. His spiritual coping mechanism—Scientology-coded and lava-lamp-adjacent as it is—becomes the emotional centerpiece, and you know what? I actually kind of respect how the group, Jeff notwithstanding, makes an effort to honor his beliefs. Say what you will about Pierce and his religion's blatant allegory for Scientology, this was the man who in season one called failure "living," so I think he doesn't really need lessons in embracing life. I don't think he's dumb enough to really think that his mom's soul was trapped in a lava lamp as particles and whatnot; just let the man deal with his mom's passing in his own way. Even if he’s being swindled by some pseudo-cult, at least he’s finding comfort. And considering how often sitcoms default to “religion = punchline,” it’s nice to see that taken just seriously enough.

And speaking of subtlety (or the lack thereof), there's Abed's clever little side plot—completely invisible unless you’re looking for it—where he helps a pregnant woman, ultimately delivering her baby in the background of everyone else's angsty drama, Hilary Winston's own not-so-subtle commentary on how we're so focused on death we missed life happening in the background. Clever, but a little pretentious, like someone patting themselves on the back in the writer’s room:

“See what we did there?” Still, credit where it’s due—it’s probably the episode’s most quietly profound idea, even if it's buried behind lava lamps and forced sitcom tropes.

In the end, this episode isn’t terrible, but it

is a letdown. For a show that usually takes pride in skewering convention and elevating tropes into art,

“The Psychology of Letting Go” feels weirdly safe, superficial, and more than a little smug. It preaches life over death, but forgets to live a little itself.